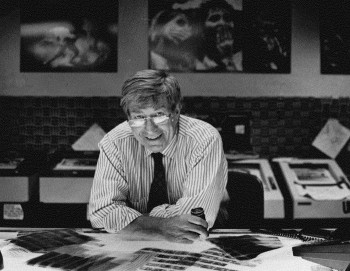

Bill Snead

Bill Snead is one of those guys who proved that you CAN go home again.

In 1954, at 17, he began his career in journalism as a darkroom boy at The Lawrence Journal-World. His boss was Rich Clarkson, five years his senior. After two or three years, Clarkson was developing bigger plans for his vision of photojournalism, which he presented to the publisher of The Topeka Capital-Journal, who signed on. Rich moved to the state capitol and hired Bill to join him there.

“My good fortune began when I was hired by the Journal-World’s photo-boss-from-Hell, Rich Clarkson,” Bill wrote on his Web page years later. “I worked for him nine years in Lawrence and Topeka. ’That’s good enough,’ was not in his vocabulary. His emotional kicks in the (butt) gave me a head start in a trade I care for as much today as I did a hundred years ago.” The Topeka Capital-Journal was beginning to gain a reputation as one of the ten best picture-producing newspapers in the country.

In spite of Rich telling his photographers that this was the best place to work, Bill decided he had to see for himself. He left Kansas in 1964 to become Director of Photography at The Wilmington (Del.) News-journal. The next year they sent him to Vietnam for a brief stint covering Delaware troops, an introduction to war and death that served him well. For three years, he was NPPA’s northeast regional photographer of the year. But he wanted to do more. Bill returned to Vietnam in 1968, this time for United Press International as its Saigon bureau chief. He got there shortly before the Tet offensive. Believing that readers didn’t want to see just photos of burning villages and the destruction of war, he balanced those with images of everyday life in a war zone. He handled photographs documenting some of the heaviest fighting in the entire war.

After two years in Vietnam, UPI brought him back to the U.S. as photo editor in their Chicago office. He covered Chicago’s massive ticket tape parade welcoming the Apollo 11 astronauts’ return to earth.

After a short stint as a picture editor at National Geographic, he landed at The Washington Post in 1972.

He began a significant 21-year stay there, serving as a staff photographer, Assistant Managing Editor for photography and graphics, and as a writer. He definitely caught the attention of Ben Bradlee, The Post’s editor, who wrote in a letter, “Something to tell you about Bill Snead… he is quite simply one of the world’s sweet guys on top of one of the really great talents of his generation.”

Bill planned to take a European vacation to Romania in 1991 in hopes of pitching the Post a story on Gypsies. The Post offered to pay his plane ticket if he would stop in the Balkans and cover the ethnic conflicts. This was the beginning of the end for Yugoslavia. While in Albania Bill heard about the conflict involving the Kurds. He called the Post and offered to cover this too. Working his way to Turkey, he covered the million Kurdish refugees driven out of Iraq into Turkey, found ways to process his film, made prints and got them transmitted back to The Washington Post. Over three hectic weeks, The Post published 33 of his photographs from the crisis. Many were the first and only of their kind.

The following year, Bill won the White House News Photographers’ top award, their Newspaper Photographer of the Year. He was also a runner-up for that year’s Pulitzer Prize for news photography.

He won recognition and many awards throughout his six-decade career with his work appearing in national and international publications. Aside from wars, he covered high school sports and Superbowls, national political conventions and rodeos. He photographed Mother Teresa standing on a box to reach the podium for an address in Washington and the two killers of the Clutter family in Kansas that Truman Capote chronicled in his book, “In Cold Blood.”

“He had the gift of empathy,” said Dick Swanson, a former LIFE magazine photographer who worked in Vietnam with Bill. “His photography was people… their joys, their sorrows.”

“Bill Snead was a unique individual, usually with a twinkle in his eye and quick with an interesting story,” said Dolph Simons Jr., publisher of The Lawrence Journal-World.

In 1993 Simons invited Bill to “come back home” and “run our newsroom.” Bill took him up on it and arranged to take a sabbatical from The Post. He returned to his hometown newspaper, where he started as a teenager 39 years earlier. This time as Deputy editor, a newly created role for Bill. He was a mentor, coach, supervisor of photographers and role model. He was free to take on an occasional self-assigned project of interest. Several were quite in depth, cancer survivors and a German Mennonite community, people reclusive at first until Bill let them get to know him.

Along with his newsroom responsibility Bill also taught classes at the University of Kansas in both the Journalism School and the Fine Art and Photography program. No surprise, the sabbatical led to his retirement from the Washington Post and a return to his hometown, working at his local, hometown newspaper for 15 more years.