What happens when a newspaper closes or merges?

By Taylor Brown, Flipboard

In the past decade, hundreds of local U.S. newspapers have closed or merged. What happens to the communities they leave behind?

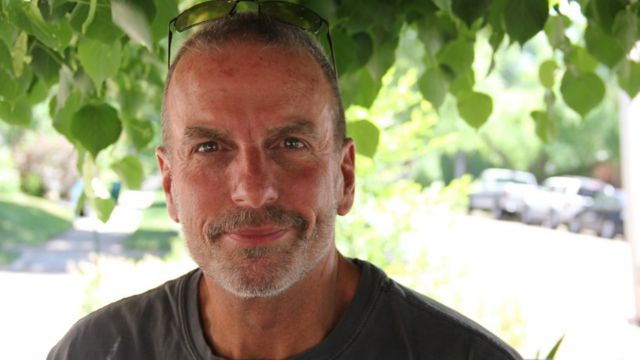

A hundred and twenty years ago, a wooden auditorium was built in the hills of Boulder, Colorado, as part of the Chautauqua movement, a lecture circuit/educational variety show for rural communities. In early June, Dave Krieger got on stage in the Chautauqua auditorium to tell the city's residents why he got fired from the local newspaper - and why he's worried about the future of local news in the U.S.

Boulder isn't an average American town - the city of 100,000 has multiple federal research centres, a growing tech scene and a median single-family home price above $1m (£752,000) - but its daily newspaper is following a path of decline that many local news outlets have trod already - some all the way to closure. That newspaper, the Daily Camera, was founded right before the Chautauqua, as Boulder grew.

Now some of the community's residents are asking - how long will the 128-year-old paper last?

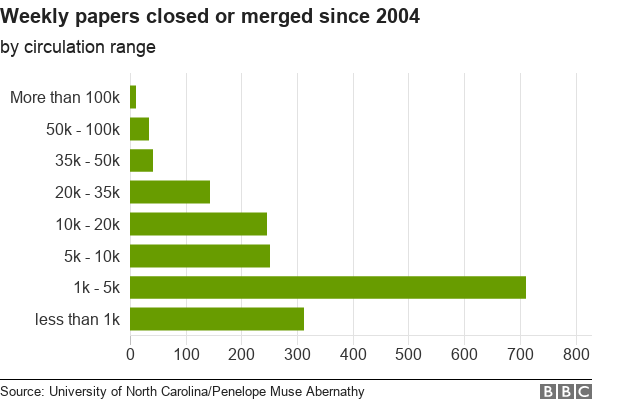

About 1,800 local papers have closed or merged since 2004, according to data from researchers at University of North Carolina. The reasons for newspaper closures are well-known: internet advertising destroying the traditional business models; readers moving towards more online and more free news. In Boulder and in nearby Denver, there's also a question of ownership.

But what's less well-known is the impact on communities who lose a local paper.

Ten years ago, a natural experiment into this question happened in Denver. The Rocky Mountain News, one of the city's two competing papers, went under, shutting down a newsroom of 200.

Susan Greene, then a reporter and columnist for the Rocky's competitor, the Denver Post, wasn't celebrating.

"Journalism is a competitive enterprise and so we were always free to write whatever we needed to, write whatever the story called for," she says.

"When they went under it was just was clear that that dynamic would change, so that if the governor or the mayor or [district attorney] or some mogul in town didn't want a story, or some advertisers didn't want a story, it would be much easier for the management to acquiesce."

Years later, Lee Shaker, who studies politics and media at Portland State University, found changes outside of the newsroom as well.

Self-reported measures of civic engagement - like contacting an election official or attending a local civic organisation - dropped in Denver after the Rocky shut down. Within two years, it had only rebounded by half.

More recently, political scientists Jennifer Lawless and Danny Hayes studied the effect of both closures and curtailed coverage across America on elections for U.S. Representatives. Those races are for national office, but their voters are local.

Hayes says when papers close or cut coverage, people are less able to identify who's running, know the candidate's issue positions and, ultimately, are less likely to vote.

"When local papers cut coverage there's essentially nothing to take its place in these local communities," he says, adding while there have been many online local news experiments they tend to be in already media-rich environments or not as focused on public affairs.

This effect happens to everyone, Hayes says, even those who are considered politically engaged.

"I suspect over the long term, people who are pretty politically engaged figure out ways to sort of maintain their level of participation," he says.

"I'm not sure they'll be necessarily as knowledgeable as they were."

There are other effects too. A recent study found cities' borrowing costs to build projects like roads and schools rose after newspapers closed - making those projects more expensive to taxpayers. As similar areas without a newspaper closure did not see those effects, they theorise that the loss of scrutiny on local government led to more mismanagement of public funds.

And epidemiologists are worried about growing blind spots in health - whether its food poisoning or Zika - because of local news closures.

Penelope Muse Abernathy, a professor and researcher at the University of North Carolina, says the closure of community newspapers means more than a loss of information.

Local news sets the agenda for public debates by bringing particular issues to public attention, encourages regional business development by connecting local businesses with local residents (whether through ads or coverage) and can reflect what's similar or different about a national problem on the local level, she says.

"A strong local newspaper shows you how you are related to people you may not know you're related to," Abernathy says.

It's a Saturday morning in Boulder and the farmers market is packed, stalls selling everything from flowers to honey to freshly-butchered meat. A guitarist plays in one section, an oboe and clarinet duo in another other. Families eat picnics in a nearby park abutting Boulder creek, where young people ride downstream on inner tubes.

Susan Seaport is gathering signatures from fellow Boulderites when I stop to talk to her. The petition calls for a moratorium on permitting fracking wells close to populated areas. It's a contentious issue across Colorado's Front Range as both the population and the natural gas market surges - one of those regional issues that has a local impact.

Susan's a Daily Camera subscriber, but she mentions Boulder's local paper recently raised the subscription price by 25 percent.

"It isn't cheap to begin with," another woman says.

Will either of them keep their subscription?

"It's a dialogue in my household," Susan says.

"In every household," a man with them adds. But all seem reticent to drop the paper entirely.

It's not unsurprising that most of the people I spoke to who subscribe to the Camera are over 50. Around the farmers market, younger Boulderites are certainly aware of the Camera - but aren't rushing to subscribe.

One woman says she takes a "quick look" at the Camera online. "But there's only so many looks before they charge you... beyond that, I don't care."

A man painting the scene at the farmers market says the articles are "kind of short" and "don't have enough substance".

Another woman outside Dave Krieger's talk said she's not an "avid reader" but follows their journalists on Twitter. "You hear a tidbit and then you search online," she says.

While technological and economic forces have done a number on local newspapers, some are still surviving, largely on loyal subscribers and a lack of true competition at the local level. Of the papers that remain, they are increasingly sold off to a new kind of newspaper owner.

The Camera, along with 96 other local papers across the U.S., including the neighboring Denver Post, is part of the Digital First Media chain.

DFM is majority-owned by Alden Global Capital, a hedge fund based in New York. This is not a unique situation - more than 1,000 papers in the U.S. (or 15 percent of all papers in the U.S.) are owned by investment groups, according to Abernathy's research.

Critics accuse these owners of effectively using newspapers as a cash point - slashing staff and raising subscription prices in service of profits notably higher than successful national papers who have seen growth in their subscriber base.

"Not only are these margins aggressive, there's no reinvestment into these papers," Abernathy says.

For years, newspaper staff considered fights about staff cuts and ownership decisions an internal matter. For the papers owned by Alden, however, that changed in a big way in April.

The Denver Post splashed their op-ed section with a picture of their staff taken in 2013, right after the paper had won a Pulitzer, but digitally removed every single person who had been laid off or left since that day - the result was sparse. The section's three editorials, including one signed by the paper's editorial board, accused Alden of a "cynical strategy" of reducing the paper while increasing subscription rates, and then "pumping hundreds of millions of dollars of its newspaper profits into shaky investments completely unrelated to the business of gathering news."

"The @denverpost is being murdered by its owners," one reporter tweeted.

The Post's editorial board said they were deliberately sounding the alarm now - before the paper went under, leaving Denver, a city of 700,000, without a single daily newspaper.

The staff at the Camera had similar worries. When Dave Krieger arrived to become the editorial page editor in November 2014, the paper had already sold off their historic downtown building and cut staff.

There were a few more layoffs, but increasingly, people weren't replaced if they left.

"We were down, on a good day, to six reporters in the newsroom," Krieger says. "You're talking about city hall, cops, courts, public education, one science reporter, one business reporter in a community that considers itself the high tech and start-up capital of Colorado."

That level of staffing, he says, meant the paper was only covering the very basics of what was happening in town.

"No extras, no enterprise, no investigative."

Krieger had earlier been in touch with a reader who'd objected to some of his previous editorials, but who was frustrated about why the paper was getting more expensive and yet smaller. So he sent the man coverage about DFM's owners that had started to percolate through national magazines.

Alden had started to gain attention through the investigative work of Julie Reynolds, a former reporter at a DFM-owned paper, who now reported for a union-backed effort to find out more about the chain's owners.

The reader was shocked.

"This was a guy very plugged into municipal politics," Krieger says. "And he had absolutely no idea."

For Colorado journalism week, he wrote an editorial criticizing Alden and calling for local ownership of the Camera. He says the publisher refused to run it.

So he posted it on his own website. And then he got fired.

Alden has not responded to multiple BBC requests for comment. The publisher of the Camera told Dave Krieger he was fired because he used company time for the editorial that was eventually published elsewhere, but refused to comment to the BBC when reached by email.

Alex Burness was the city hall reporter at the Camera until May. He says, in spite of the cuts, the paper is still the most important local news source in the community: "If something's going on - you're finding out about it in Camera."

But Burness also says the pressure for the small staff to put out a daily newspaper meant there were "endless stories" he didn't have the time to report.

What's happening in Boulder - some recent headlines from the Camera

- "Neighbors of Eben G. Fine [park] aren't celebrating Boulder park's growing popularity with July 4 crowds"

- "Teen suffers minor injuries in fall from Boulder's Second Flatiron"

- "Mustard's Last Stand marks 40 years of hot-dog slinging in Boulder"

- "Boulder-born Shambhala International hiring investigator to review allegations of sexual misconduct"

Both Burness and Krieger are surprised given Boulder's money and tech know-how, that the Camera hasn't attracted an online competitor.

"It's sort of surreal feeling being in a place where there's so much money and so much interest in local news," but no movement to start something new, Burness says. "It's like starving inside a grocery store."

There's certainly a lot of energy around local news start-ups down the road in Denver.

Denverite has provided online coverage for the state's largest city for two years. In the past few weeks, a number of Denver Post reporters and editors were lured away by the blockchain editorial start-up Civil to create the Colorado Sun.

And the Colorado Independent covers stories across the state, funded entirely by foundation and individual donation support. Susan Greene is now its editor.

She says the Independent is not the site that's going to go to every city council meeting or every school board.

"We cover really local issues when it has a huge impact on the rest of the state or we can cover state policy issues."

Greene says Independent readers respond to their coverage because it's different. That includes a strong following with African Americans, younger and newer Coloradoans and LGBT readers.

"Even though we had two very robust newspapers [in Denver], it's not necessarily true that those papers were doing a fantastic job covering certain communities of color or some poorer communities in the state."

The notion of being a newspaper of record is a "lovely, beautiful idea," she says. "But in practice, it's not necessarily being carried out."

Younger readers are especially hungry for information, she says, but not in the way that a traditional community newspaper would approach it.

"People want story," she says. "They want story told with soul."

But nationwide, there's been no mass replacement of local newspapers. Non-profit online sites are largely based in major metro areas.

As of 2011, all news radio stations cover only 40 percent of the U.S. Local TV stations often have similar staff sizes as newspapers but cover a larger area, often focusing on weather, sports and individual cases of crime.

Newspapers can also reinvest in themselves, Abernathy says, but not by following old patterns.

"One of the things we have to acknowledge is our news had been subsidized by advertising," she says, and changing a local newspaper's business model avoid to relying on advertising is the first step.

The question is - will Boulder - and thousands of communities around the U.S. - figure it out before their daily newspaper is gone?